The Link Between Panic Attacks and Insomnia: Understanding the Bidirectional Sleep-Anxiety Cycle

Story-at-a-Glance

- The link between panic attacks and insomnia operates as a bidirectional cycle. Each condition worsens the other through shared neurobiological pathways.

- Research reveals that 52% of panic disorder patients experience nocturnal panic attacks. Additionally, 80% report significant insomnia symptoms.

- Hyperarousal in brain circuits regulating emotion appears more central to this connection than traditional sleep-wake regulation systems.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) shows promising results in reducing both sleep disturbances and panic symptoms. It does so without directly targeting anxiety.

- Current mental health trends show anxiety affecting 43% of adults in 2024 – up from 32% in 2022. This makes understanding this relationship more critical than ever.

Main Body

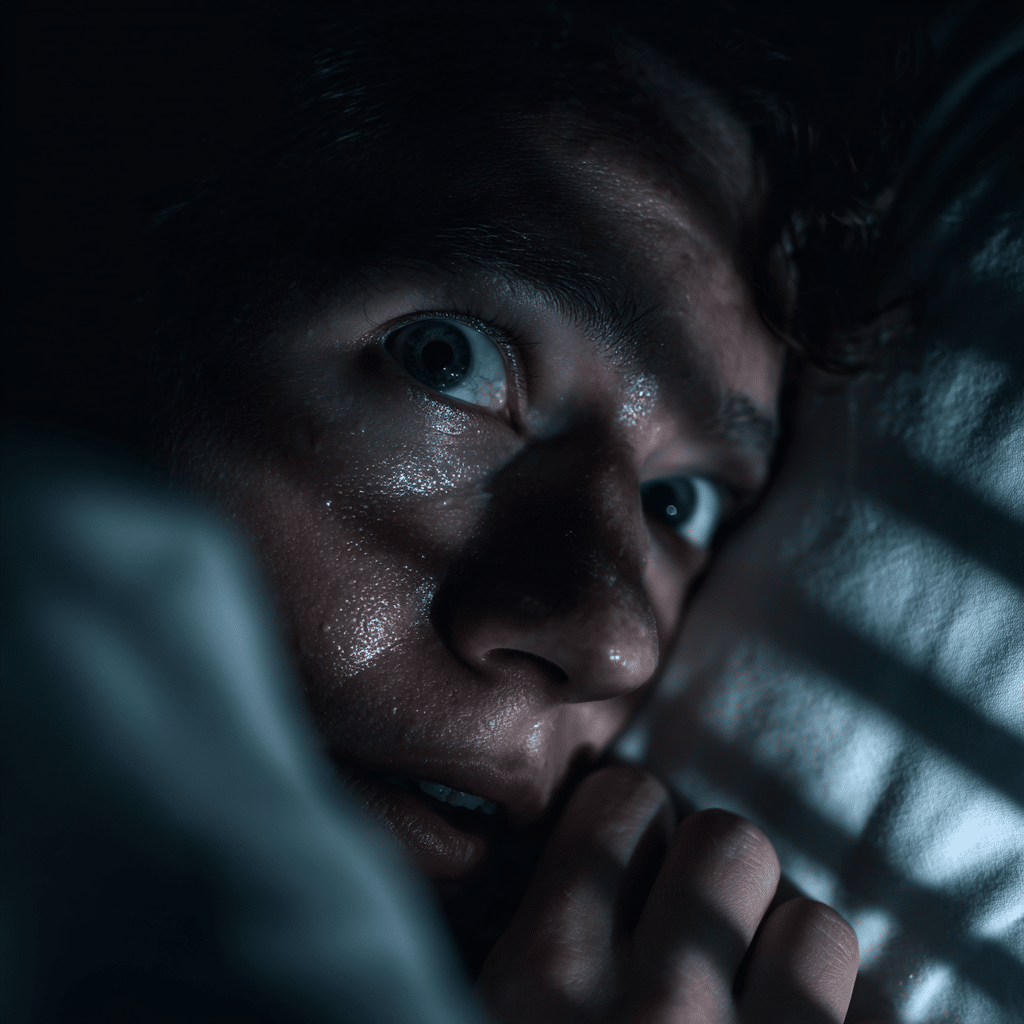

Picture this: You’re awakened at 2 AM by an overwhelming surge of terror. Your heart races uncontrollably. Sweat drenches your sheets. You’re gasping for air despite being in the safety of your own bedroom. You don’t remember having a nightmare. The terror simply erupted from nowhere during what should have been peaceful sleep.

If you’ve experienced a nocturnal panic attack like this, you’re far from alone. What many people don’t realize is that the link between panic attacks and insomnia represents one of the most complex challenges in sleep medicine today. It’s also one of the most clinically significant. The relationship isn’t simply that panic attacks disturb sleep. It’s that disturbed sleep can actually trigger panic attacks. This creates a vicious cycle that’s remarkably difficult to escape without proper understanding and intervention.

The Science Behind the Sleep-Panic Connection

Recent groundbreaking research has fundamentally changed how we understand the link between panic attacks and insomnia. A comprehensive 2024 systematic review led by Dr. Laura Palagini at the University of Pisa examined 93 studies on insomnia and anxiety-related disorders. This included panic disorder. The findings paint a compelling picture: this connection runs much deeper than previously imagined.

Here’s what makes this relationship particularly fascinating (and frustrating). A meta-analysis of sleep disturbances in panic disorder found that individuals with panic disorder had significantly longer sleep onset latency. They also had poorer sleep efficiency and shorter total sleep time compared to healthy controls. More striking? Among panic disorder patients, 52.1% experienced nocturnal panic attacks—sudden episodes of intense fear erupting during non-REM sleep stages.

But why does this happen? The answer lies in what researchers call hyperarousal—a state where your brain’s threat-detection systems remain perpetually on high alert. Professor Dieter Riemann at the University of Freiburg, whose work has shaped modern insomnia research, offers crucial insight. He suggests that the vulnerability to develop insomnia may reside in brain circuits regulating emotion and arousal. It’s not primarily in those controlling circadian and homeostatic sleep regulation. Your panic-prone brain might be fundamentally primed to both struggle with sleep and experience panic—a double vulnerability that creates the perfect storm.

Save This Article for Later – Get the PDF Now

When Sleep Becomes the Trigger

Research published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine reveals something counterintuitive: nocturnal panic attacks typically occur during transitions between light and deep sleep. They happen most commonly in the first half of the night. They strike when you’re most vulnerable—when conscious control gives way to the automatic processes of sleep.

Dr. Abhinav Singh, Medical Director of the Indiana Sleep Center, notes that distinguishing between daytime and nocturnal panic attacks helps narrow the probable causes. This leads to more targeted treatment. Nocturnal episodes may be more likely to involve feelings of choking. They also create such intense fear that individuals develop somniphobia—a fear of sleep itself.

Consider what happened to participants in a recent Korean clinical study. Researchers examined 110 consecutive patients with diagnosed panic disorder. They found that 80% had comorbid depression. Additionally, 80.9% experienced insomnia. Most revealing? The study demonstrated that insomnia mediated the relationship between panic symptom severity and depression. In simpler terms: the sleep problems weren’t just a side effect. They were actively driving the worsening of both panic and depressive symptoms.

The Anxiety Epidemic of 2024-2025

Understanding the link between panic attacks and insomnia has become increasingly urgent. The American Psychiatric Association’s 2024 annual poll revealed that 43% of American adults report feeling more anxious than the previous year. This is a dramatic increase from 37% in 2023 and 32% in 2022. Key anxiety contributors? Current events, stress, and notably, poor sleep.

This represents more than statistical curiosity. We’re witnessing a genuine mental health crisis where sleep disturbances and anxiety disorders feed into each other at a population level. The World Health Organization estimates that 275 million people globally live with anxiety disorders. The prevalence increased from 3.7% to 4.4% worldwide between 1990 and 2021.

Breaking the Cycle: What Actually Works?

Here’s where the research gets genuinely hopeful. A fascinating Swedish study examined 24 participants diagnosed with both insomnia disorder and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Researchers provided Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I). But here’s the remarkable part: they didn’t directly target the anxiety symptoms.

The results? Approximately 61% of patients responded to CBT-I. Between 26-48% achieved remission of insomnia. But the real surprise was that participants also showed moderate to large improvements in GAD symptoms, depression, functional impairment, and quality of life. This happened despite the intervention focusing exclusively on sleep. Additionally, you might find our article on insomnia and anxiety relief techniques for stressed individuals helpful for practical applications of these principles.

This brings us to an important professional observation. While these findings are encouraging, we must acknowledge the limitations in current research. Most studies on the link between panic attacks and insomnia are cross-sectional. This makes it challenging to establish clear causality. Does poor sleep trigger panic, or does panic create sleep problems? The answer appears to be “both.” But determining which dominates in individual cases remains difficult. Professor Colin Espie at Oxford University, a pioneer in digital cognitive behavioral therapy, emphasizes that treatment must be tailored to individual presentations. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution.

Practical Pathways Forward

So what can you do if you’re caught in this cycle? The evidence suggests several approaches:

- Sleep-focused interventions work. Even without directly addressing panic symptoms, improving sleep architecture can reduce anxiety and panic frequency. This challenges the traditional assumption that you must “fix the anxiety first.”

- Understand your vulnerability. Some people are genetically and neurobiologically predisposed to both insomnia and panic. Recognizing this isn’t defeatist. It’s empowering because it shifts focus from “what’s wrong with me?” to “how does my system work?”

- Avoid the medication trap. While benzodiazepines may offer short-term relief, research consistently shows they worsen outcomes over time for people with panic disorder who also struggle with sleep. They disrupt sleep architecture. They can increase panic severity.

- Consider the timing. Nocturnal panic attacks typically occur in the first half of the night during sleep stage transitions. Understanding this pattern can help both you and your healthcare provider develop targeted interventions.

Does this mean everyone experiencing the link between panic attacks and insomnia will respond to sleep-focused treatment? Not necessarily. That’s an honest limitation we must acknowledge. Some individuals require direct panic-focused interventions before sleep improves. Others need medication alongside therapy. What’s revolutionary is recognizing that we have multiple entry points into this cycle. Improving sleep represents a powerful, often underutilized lever.

The Road Ahead

The convergence of rising anxiety rates and our deepening understanding of sleep neurobiology creates both challenge and opportunity. We now recognize that the link between panic attacks and insomnia isn’t a simple cause-and-effect relationship. Rather, it’s an intricate dance between multiple brain systems—threat detection, emotion regulation, circadian rhythms, and sleep-wake control.

Current research, including ongoing work examining brain mechanisms underlying insomnia vulnerability, suggests we’re on the cusp of more personalized treatments. These will be neurobiologically-informed. Scientists at the Salk Institute recently identified novel brain pathways mediating panic-like symptoms in animal models. These pathways are distinct from the traditional “fear center” of the amygdala. Such discoveries may eventually translate into new treatment targets.

For now, the message is clear. If you’re struggling with both panic and sleep problems, you’re dealing with a genuine medical condition with solid neurobiological underpinnings. It’s not weakness. It’s not imagination. It’s not “just stress.” And perhaps most importantly—treating one can help resolve the other. This offers hope that breaking into this cycle is possible from multiple angles.

FAQ

Q: What exactly is the link between panic attacks and insomnia?

A: The link between panic attacks and insomnia is bidirectional. This means each condition can trigger and worsen the other. Panic disorder creates hyperarousal that makes falling and staying asleep difficult. Meanwhile, chronic sleep deprivation lowers the threshold for panic attacks. Research shows 52.1% of panic disorder patients experience nocturnal panic attacks. Approximately 80% have significant insomnia symptoms.

Q: How do nocturnal panic attacks differ from regular nightmares?

A: Nocturnal panic attacks involve clearly waking up from sleep with intense fear and physical symptoms like racing heart, sweating, and difficulty breathing. Unlike nightmares (which occur during REM sleep and are remembered as disturbing dreams), nocturnal panic attacks typically happen during non-REM sleep transitions. They don’t involve dream content. People remember nocturnal panic attacks vividly. This can create fear of sleep itself.

Q: Can treating insomnia help reduce panic attacks?

A: Yes. Research demonstrates that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) can reduce both insomnia and anxiety symptoms. This happens even without directly targeting panic. In studies, 61% of patients with comorbid insomnia and generalized anxiety disorder responded to CBT-I. They showed improvements in anxiety, depression, and quality of life. This suggests that improving sleep architecture can break the cycle from the sleep side.

Q: What is hyperarousal, and why does it matter?

A: Hyperarousal refers to a state where the brain’s threat-detection systems remain excessively active. This happens even when no real danger exists. In the context of panic and insomnia, hyperarousal keeps both cognitive and physiological systems on “high alert.” This prevents the natural relaxation necessary for sleep. It simultaneously lowers the threshold for panic responses. It represents the shared neurobiological mechanism linking these two conditions.

Q: Are there genetic or biological factors that predispose someone to both conditions?

A: Yes. Research indicates heritability coefficients between 42-57% for chronic insomnia. This means that genetic factors account for roughly half the risk of developing chronic sleep problems. Family studies suggest genetic components to panic disorder as well. Brain imaging studies show that individuals vulnerable to both conditions may have differences in brain circuits regulating emotion and arousal. This particularly involves the amygdala, locus coeruleus, and prefrontal cortex. This doesn’t mean these conditions are inevitable. Rather, some individuals have neurobiological vulnerabilities that make the sleep-panic cycle more likely. Think of it like having a predisposition: if you have family members with insomnia or panic disorder, you may have inherited a more sensitive nervous system. This system is more reactive to stress.

Q: Should I be concerned about medications for panic and sleep?

A: Research shows that while benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine receptor agonists may provide short-term relief, they can worsen long-term outcomes for people with panic disorder. These medications disrupt natural sleep architecture. They may increase panic severity over time. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are generally preferred for panic disorder. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before starting or stopping any medication.

Q: What does “CBT-I” mean, and is it different from regular therapy?

A: CBT-I stands for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia. It’s a specialized form of cognitive behavioral therapy that focuses specifically on changing thoughts and behaviors that interfere with sleep. Unlike general talk therapy, CBT-I uses structured techniques specifically targeting sleep problems. These include: (1) sleep restriction—temporarily limiting time in bed to match actual sleep time, strengthening the bed-sleep connection; (2) stimulus control—retraining your brain to associate bed with sleep rather than wakefulness; (3) cognitive restructuring—identifying and changing unhelpful thoughts about sleep. It’s considered the first-line treatment for chronic insomnia. It has evidence showing benefits for comorbid anxiety as well.

Q: What do terms like “sleep architecture,” “sleep stages,” and “REM sleep” mean?

A: Sleep architecture refers to the overall structure and pattern of your sleep throughout the night. Your brain cycles through different sleep stages—think of them as different depths of sleep. There are four main stages: Stage 1 (lightest sleep, just drifting off), Stage 2 (light sleep where you spend most of the night), Stage 3 (deep sleep, hardest to wake from), and REM sleep (Rapid Eye Movement sleep, where most dreaming occurs). During REM sleep, your eyes literally move rapidly under your eyelids. A healthy night involves cycling through these stages multiple times. Nocturnal panic attacks typically occur during transitions between these stages. They particularly happen when moving from light (Stage 2) to deep sleep (Stage 3).

Q: What does “comorbid” mean when discussing panic and insomnia?

A: “Comorbid” simply means two or more medical conditions occurring together in the same person at the same time. When we say panic disorder and insomnia are comorbid, we mean a person has both conditions simultaneously. This is different from one condition causing the other. Comorbidity recognizes that both are present. They often interact with and influence each other, regardless of which came first.

Q: What are “sleep onset latency” and “sleep efficiency”?

A: Sleep onset latency is the technical term for how long it takes you to fall asleep after getting into bed and turning off the lights. Basically, it’s the time from “lights out” to actually being asleep. Sleep efficiency is a percentage that measures how much time you’re actually sleeping compared to how much time you spend in bed. For example, if you’re in bed for 8 hours but only sleep for 6 hours, your sleep efficiency is 75%. People with insomnia typically have longer sleep onset latency (taking a long time to fall asleep). They also have lower sleep efficiency (spending lots of time awake in bed).

Q: What does “circadian” mean in the context of sleep?

A: “Circadian” refers to your body’s internal 24-hour clock—your natural biological rhythms that tell you when to feel sleepy and when to feel alert. Your circadian system responds primarily to light and darkness. This is why you naturally feel more awake during the day and sleepier at night. Circadian rhythms control not just sleep-wake cycles but also body temperature, hormone release, and other important functions. When researchers discuss circadian sleep regulation, they’re talking about how this internal clock influences when and how well you sleep.

Q: What is “somniphobia” and how does it relate to panic attacks?

A: Somniphobia is an intense fear of sleep or falling asleep. It can develop after experiencing nocturnal panic attacks because the attacks are so terrifying that people become afraid of going to sleep. They worry another attack will occur. This creates a particularly vicious cycle: fear of sleep makes it harder to fall asleep, sleep deprivation makes panic attacks more likely, and more panic attacks intensify the fear of sleep. It’s a recognized anxiety disorder that often requires specialized treatment. This treatment addresses both the panic symptoms and the sleep avoidance.

Q: What are benzodiazepines, and why are they concerning for panic and sleep?

A: Benzodiazepines are a class of sedative medications (like Xanax, Valium, or Ativan) that calm the nervous system by enhancing a brain chemical called GABA. While they can provide quick relief from panic symptoms and help with falling asleep, research shows they cause problems when used long-term for panic disorder. They disrupt natural sleep architecture—meaning they change the normal cycling through sleep stages. They can actually increase panic severity over time. People may also develop tolerance (needing higher doses for the same effect) and dependence. For panic with insomnia, SSRIs (antidepressants) are generally safer and more effective long-term.

Q: What are the brain regions mentioned—amygdala, locus coeruleus, and prefrontal cortex?

A: These are key brain structures involved in emotion, arousal, and fear responses. The amygdala is often called the brain’s “fear center.” It detects threats and triggers your fight-or-flight response during panic. The locus coeruleus is a small cluster of neurons that produces noradrenaline (a stress hormone) and helps maintain alertness. When overactive, it contributes to hyperarousal and makes both panic and insomnia worse. The prefrontal cortex is the “thinking” part of your brain at the front that helps regulate emotions and make rational decisions. When it’s not functioning optimally, it struggles to calm down the amygdala and locus coeruleus. In people vulnerable to panic and insomnia, these three regions often show altered activity patterns.

Q: What is “homeostatic sleep regulation” and why does it matter?

A: Homeostatic sleep regulation is your body’s natural “sleep pressure” system. The longer you’re awake, the more your body builds up pressure to sleep, like a battery running down. This is why you feel increasingly tired as the day goes on. When you sleep, this pressure is released and resets for the next day. The article mentions that in people with insomnia and panic, the problem may be less about this natural sleep pressure system. It’s more about emotional and arousal systems being overactive. In other words, even when your body is tired and ready for sleep (homeostatic pressure is high), your hyperaroused emotional systems keep you awake. It’s like having your foot on both the gas and brake pedals simultaneously.

Q: What are “systematic reviews” and “meta-analyses” and why are they important?

A: These are types of research studies that are considered particularly reliable evidence. A systematic review is when researchers carefully search for all available studies on a topic (like insomnia and panic disorder). They evaluate their quality and summarize what the combined evidence shows. A meta-analysis goes a step further by statistically combining results from multiple studies. This provides stronger, more precise conclusions than any single study could provide. When the article mentions “a 2024 systematic review examined 93 studies” or “a meta-analysis found that 52.1% of panic disorder patients experience nocturnal panic attacks,” these represent high-quality evidence. This evidence is synthesized from many individual research projects, making the findings more trustworthy than a single study alone.

Q: What does “cross-sectional study” mean?

A: A cross-sectional study is research that looks at a group of people at a single point in time, like taking a snapshot. It can show that two things occur together (like panic attacks and insomnia). However, it can’t prove which came first or whether one caused the other. That would require following people over time. When the article mentions limitations of cross-sectional research on the panic-insomnia link, it means we can see these conditions frequently occur together. But determining the exact cause-and-effect relationship requires longer-term studies that track people over months or years.

Q: How long does it typically take to see improvement?

A: For CBT-I, most people begin seeing improvements within 4-8 weeks. This varies individually, though. Some experience relief sooner. Others require more time, especially if panic disorder is severe. The key is consistency with the behavioral interventions. For panic-focused treatments, timelines also vary. Research suggests that addressing either condition (sleep or panic) can create positive momentum for improving both.