Why Home Sleep Tests for Narcolepsy Diagnosis Accuracy Fall Dangerously Short—And What Patients Really Need to Know

Story-at-a-Glance

- Home sleep tests lack the electroencephalogram (EEG) recording capability essential for diagnosing narcolepsy, measuring only breathing and oxygen levels rather than brain activity and REM sleep patterns

- The widespread use of home testing for excessive daytime sleepiness has exacerbated the under-recognition of narcolepsy, with patients frequently misdiagnosed with sleep apnea and treated inappropriately for years

- Even the gold-standard Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) used in sleep laboratories has significant limitations, with false-positive rates of 2.5-4.7% and false-negative rates of 7-20%

- Real-world cases demonstrate that patients with both narcolepsy and sleep apnea often have their narcolepsy completely missed when only home testing is performed, leading to treatment that addresses only part of their condition

- The average time from symptom onset to accurate narcolepsy diagnosis remains 8-15 years, with this diagnostic delay significantly worsened by the increasing reliance on home sleep testing that cannot detect the disorder

- Comprehensive sleep laboratory testing with polysomnography followed by MSLT remains the only validated pathway for narcolepsy diagnosis, despite ongoing research into alternative biomarkers

When a 30-year-old woman I’ll call Mrs. K finally underwent proper sleep laboratory testing after years of unexplained exhaustion, the results shocked everyone involved. Despite having been treated for sleep apnea for nearly a decade following a home sleep test, she had narcolepsy all along—a discovery that fundamentally changed her treatment and, ultimately, her life. Her story isn’t unique; it’s emblematic of a growing crisis in sleep medicine where the convenience and cost-effectiveness of home sleep tests for narcolepsy diagnosis accuracy have created a dangerous blind spot.

The promise of home sleep testing seemed straightforward: bring diagnostic capabilities directly to patients’ bedrooms, reduce costs, and improve access to care. Yet this technological convenience has inadvertently obscured a critical limitation—home sleep tests cannot diagnose narcolepsy, period. And as these devices proliferate, so too does the misdiagnosis rate for one of the most misunderstood sleep disorders.

The Fundamental Incompatibility: Why Home Tests Can’t See What Matters

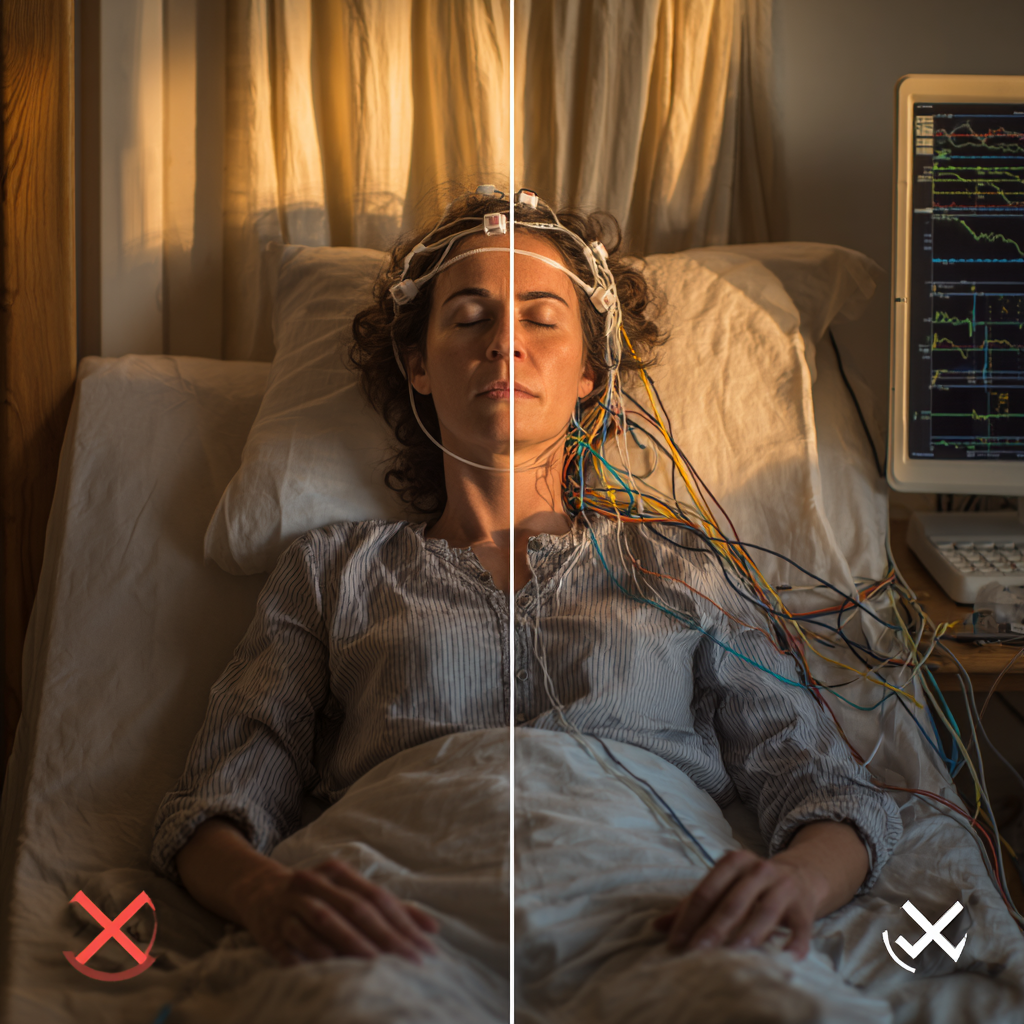

The technology gap isn’t subtle. Types 3 and 4 portable monitors commonly used for home sleep apnea testing lack the capability for electroencephalogram recording. This EEG recording is necessary for the diagnosis of narcolepsy and other sleep disorders, according to research published in the journal Sleep Medicine. This isn’t a minor technical limitation—it’s a dealbreaker.

Think of it this way: diagnosing narcolepsy through a home sleep test is like trying to diagnose a heart arrhythmia by only measuring respiratory rate. The equipment simply isn’t measuring the right physiological signals. Home sleep apnea tests only monitor breathing and oxygen levels. They cannot test for non-breathing-related sleep disorders such as narcolepsy because they don’t capture information about total sleep time, nighttime awakenings, or sleep stages.

What does narcolepsy diagnosis actually require? The answer involves understanding the disease’s neurobiological signature. Dr. Emmanuel Mignot, Craig Reynolds Professor of Sleep Medicine at Stanford University and winner of the 2023 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences for discovering narcolepsy’s cause, has spent decades unraveling this puzzle. His research revealed that narcolepsy affecting 1 in 2,000 people is caused by an immune-mediated destruction of approximately 70,000 hypocretin/orexin neurons in the hypothalamus. These neurons regulate wakefulness and REM sleep.

This neurological mechanism manifests in specific, measurable ways during sleep. People with narcolepsy enter REM sleep abnormally quickly and frequently during daytime naps—a phenomenon called sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMPs). If someone has narcolepsy, the Multiple Sleep Latency Test usually reveals that the person falls asleep rapidly (in less than eight minutes on average across naps). It also shows they enter REM sleep during two or more naps. Most people without narcolepsy take much longer to fall asleep during naps. If they do fall asleep, they rarely enter REM sleep.

Home sleep tests, designed to detect obstructed breathing, measure none of this.

The Dangerous Middle Ground: When Sleep Apnea Masks Narcolepsy

Perhaps the most insidious consequence of relying on home sleep tests for narcolepsy diagnosis accuracy concerns patients who have both conditions simultaneously. Recent research from China provides sobering data: A 2025 study documented two male patients who initially presented with symptoms suggestive of obstructive sleep apnea, including loud snoring and witnessed apneas. Despite appropriate CPAP management, both continued to experience excessive daytime sleepiness. They also reported episodes of cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and vivid dreams.

The prevalence of this comorbidity is substantial. Studies show that for adults, the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in narcolepsy type 1 ranges from 24.8% to 51.4%—meaning that up to half of people with narcolepsy also have sleep apnea. This overlap creates a perfect storm for misdiagnosis.

Here’s what happens in practice: A patient reports crushing daytime sleepiness. A home sleep test is ordered. The test comes back positive for sleep apnea. CPAP therapy begins. The patient’s sleepiness improves somewhat (because the sleep apnea is being treated), but significant symptoms remain. These residual symptoms—the cataplexy, the sleep paralysis, the hypnagogic hallucinations characteristic of narcolepsy—might be dismissed as “incomplete response to treatment” or attributed to poor CPAP compliance.

If a patient has both narcolepsy and sleep apnea, the result of the home test for obstructive sleep apnea will be positive. The patient will probably be treated with CPAP. Coexisting narcolepsy may potentially go undiagnosed if the treatment improves the patient’s excessive daytime sleepiness. Years can pass. The narcolepsy continues untreated.

Consider another documented case: An 8.5-year-old boy was misdiagnosed as having obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. He received many other diagnoses at different hospitals over a period of 3 years before the correct narcolepsy diagnosis was made. Three years of a childhood lost to misdiagnosis because the initial testing couldn’t see the full picture.

These aren’t just medical curiosities—they represent systemic failures in diagnostic pathways. When I think about the implications, I’m struck by how our well-intentioned efforts to make sleep medicine more accessible may have inadvertently created barriers to accurate diagnosis for the most vulnerable patients.

The Gold Standard’s Tarnished Crown: Even Laboratory Testing Has Limits

But even when patients do make it to a sleep laboratory—the supposed gold standard—the diagnostic journey remains fraught with uncertainty. The Multiple Sleep Latency Test, while vastly superior to home testing for narcolepsy evaluation, carries its own significant limitations.

Dr. Thomas Scammell, Professor of Neurology at Harvard Medical School and leading narcolepsy researcher, has extensively documented these challenges. In his presentation at the SLEEP 2016 meeting, Dr. Scammell noted that two or more sleep-onset REM periods occur in 13% of men and 6% of women. SOREMPs combined with MSLT latency of less than 8 minutes occurs in 6% of men and 1% of women. These percentages are larger than the estimated prevalence of narcolepsy in the population, suggesting substantial false-positive rates.

The false-negative problem is equally concerning. Research shows the MSLT may be falsely negative in a significant portion of subjects clinically suspected to have narcolepsy. One study found the test was falsely negative in 7% of narcolepsy type 1 patients. False negatives generally occur between 7% and 20% of the time. Causes include anxiety, medications, age, and environmental factors such as noise in the sleep laboratory.

Perhaps most troubling is the test-retest reliability problem. A groundbreaking study found that among 36 patients diagnosed with narcolepsy without cataplexy or idiopathic hypersomnia who underwent two MSLTs, mean sleep latencies on the first and second tests showed no significant correlation. Only 5 of 15 patients with an initial narcolepsy type 2 diagnosis demonstrated a positive MSLT upon repeat testing.

Think about that for a moment: The test we rely on to diagnose narcolepsy type 2—the form without the distinctive cataplexy symptom—produces inconsistent results more than half the time when repeated. Subsequent research confirmed that PSG and MSLT accurately and reliably diagnosed hypocretin-deficient narcolepsy type 1 (accuracy = 0.88, reliability = 0.80). However, PSG/MSLT results for patients with hypersomnolence and normal hypocretin-1 had poor reliability (0.32) and low repeatability.

Why such variability? The MSLT is exquisitely sensitive to confounding factors. Multiple SOREMPs can occur with shift work, circadian disorders, and insufficient sleep. Recent discontinuation of antidepressants or stimulants that suppress REM sleep can also cause multiple SOREMPs. Sleep apnea itself can produce false-positive results. A study analyzing data from 823 people who had repeat MSLT testing at 4-year intervals found that many with initially positive results didn’t replicate those findings—likely representing the background noise of these confounders rather than true narcolepsy.

The Human Cost: Diagnostic Odysseys and Wasted Years

The statistics on diagnostic delay are staggering and, frankly, unacceptable. From symptom onset to diagnosis, patients see multiple clinicians and wait almost 10 years on average. This means lots of misdiagnosis and suffering along the way. Recent 2024-2025 data suggests this hasn’t improved: Research shows diagnosis of narcolepsy often experiences a delay of at least ten years. It can take between 8 and 15 years after symptom onset to receive a narcolepsy diagnosis.

What fills those lost years? Misdiagnoses, primarily. A sleep clinic study examining 41 patients directly referred with a diagnostic label of narcolepsy found that only 19 (46%) were subsequently confirmed to have narcolepsy on objective testing. This means 54% had been incorrectly diagnosed. But the reverse problem is equally severe: A United Kingdom study found that half of patients in their sample population referred with narcolepsy did not have the condition when formally assessed. This implies the potential for patients to be incorrectly managed for a chronic illness while potentially having their underlying condition inadequately treated.

We’re failing in both directions simultaneously—overdiagnosing some patients while missing countless others entirely.

The rise of home sleep testing has demonstrably worsened this situation. These limitations of home sleep apnea testing, combined with its increased use for evaluation of excessive daytime sleepiness, may further exacerbate the under-recognition of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias. This occurs either as primary disorders or as comorbid disorders with obstructive sleep apnea.

I find myself wondering: How many people currently using CPAP machines actually have undiagnosed narcolepsy? How many have given up on treatment, believing themselves non-compliant or hopeless cases, when the real problem is that they were never tested for the right condition?

Similar diagnostic challenges exist with other sleep disorders requiring comprehensive evaluation. For instance, proper diagnosis of sleepwalking also requires polysomnography rather than home testing. This is because it necessitates observation of sleep architecture and behavioral events that home devices cannot capture.

Save This Article for Later – Get the PDF Now

The Path Forward: What Actually Works

So where does this leave patients with excessive daytime sleepiness? The answer requires acknowledging both what doesn’t work and what does.

What doesn’t work: Relying on home sleep tests to rule out narcolepsy. Home sleep apnea testing cannot detect narcolepsy and is not recommended if narcolepsy is suspected. These tests should not even be used to check for sleep apnea in people who may have other sleep disorders such as narcolepsy.

What does work—with caveats: Comprehensive laboratory testing. Although home sleep apnea testing may diagnose obstructive sleep apnea in appropriately selected patients, it cannot rule out or diagnose narcolepsy. Therefore, at present, polysomnography and MSLT remain the cornerstone for narcolepsy diagnosis.

But as we’ve seen, even this gold standard has significant limitations. The testing protocol matters enormously. To ensure optimal MSLT conditions, patients should discontinue antidepressants for 3 weeks and stimulants for 1 week before the test. They should also ensure adequate amounts of sleep in the week prior to the test. This can be verified through actigraphy or a sleep log.

Additionally, confirming the patient appropriately times their sleep can help ensure optimal test conditions. For example, patients with circadian phase delay should try to shift their schedule closer to usual sleep lab conditions. Alternatively, if staffing permits, the lab can try to run the polysomnography and MSLT at the patient’s typical sleep times.

Even with perfect testing conditions, clinical judgment remains paramount. The diagnosis of narcolepsy without cataplexy (type 2) is often a challenge even for highly experienced clinicians. This arises from the nonspecific nature of symptoms, the limitations of current diagnostic tests, and the lack of useful biomarkers.

For patients with clear cataplexy—the sudden loss of muscle tone triggered by strong emotions—the diagnosis is more straightforward. But cataplexy occurs in only 60-70% of narcolepsy patients, leaving a substantial population without this distinctive clinical marker.

Emerging biomarkers offer hope. Testing cerebrospinal fluid for hypocretin-1 levels can provide highly specific results for narcolepsy. Hypocretin levels are low in almost no other condition. The test requires a lumbar puncture to collect the fluid. It makes the diagnosis much clearer in some children, adults who have unusual cataplexy, and anyone who cannot discontinue medications that interfere with the MSLT.

Genetic testing can also provide supporting evidence. Almost everyone with narcolepsy type 1 carries the genetic marker HLA-DQB1*06:02 associated with the disorder. However, this gene is only a predisposing factor. Because it exists in many people without narcolepsy, it alone cannot provide a diagnosis.

Why This Matters Now: The 2024-2025 Landscape

Recent developments underscore the urgency of addressing these diagnostic shortfalls. At the 2025 World Sleep Congress, experts presented data showing patients with narcolepsy have substantially higher rates of comorbidities. These include POTS (18% for type 1 narcolepsy versus the national average), as well as increased odds ratios for depression (2.7), anxiety (1.8), ADHD, PTSD, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome.

These comorbidities themselves can obscure the narcolepsy diagnosis—or be mistaken for it. Narcolepsy is often misdiagnosed as psychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, and dissociative disorder. Misdiagnosis or diagnostic delays further contribute to impairments in productivity, academic achievement, and occupational performance.

The pharmaceutical landscape is also rapidly evolving, with multiple new treatments approved or in development specifically targeting the hypocretin deficiency at narcolepsy’s core. But these treatments can only help patients who have been correctly diagnosed in the first place.

Pediatric narcolepsy presents unique challenges. A 2024 study analyzing claims data found that narcolepsy diagnoses occurred in only 0.01% of youth, primarily during adolescence. Only half overall had evidence of the diagnostically required polysomnography with MSLT, underscoring potential widespread misdiagnosis. Diagnosing narcolepsy in children is particularly challenging due to atypical symptoms leading to frequent misdiagnosis or missed diagnoses. Only 10-15% of patients exhibit all four major features of narcolepsy, and this is even rarer in children.

What Patients Should Demand

If you or someone you love suffers from excessive daytime sleepiness that interferes with daily functioning, here’s what you need to know:

First, understand that a home sleep test—while valuable for detecting sleep apnea—cannot diagnose narcolepsy. If your home test is negative but you still have severe sleepiness, insist on comprehensive evaluation.

Second, if your home test is positive for sleep apnea and CPAP treatment helps but doesn’t completely resolve your symptoms, don’t assume you’re just a “poor responder.” Continued excessive daytime sleepiness in patients diagnosed and treated for obstructive sleep apnea may indicate comorbid narcolepsy or another sleep disorder. Demand further testing.

Third, seek evaluation at centers with expertise in narcolepsy. Not all sleep laboratories have equal experience with the condition. As we’ve seen, even the MSLT requires careful administration and interpretation to minimize false results.

Fourth, prepare thoroughly for testing. Document your sleep-wake patterns for at least two weeks beforehand. Work with your physician to safely discontinue any medications that might interfere with test results. Ensure you’re getting adequate sleep quantity in the week before testing—sleep deprivation itself can produce MSLT results that mimic narcolepsy.

Finally, be persistent. The average patient sees multiple different clinicians from time of onset of symptoms until diagnosis. If your first evaluation doesn’t provide answers, seek a second opinion. The test-retest reliability problems we’ve discussed mean that sometimes repeating the MSLT under better conditions yields different results. These may be more accurate.

The convenience of home sleep testing has genuinely revolutionized access to diagnosis and treatment for obstructive sleep apnea—one of the most common and dangerous sleep disorders. But this success story has a darker subplot: the home sleep tests for narcolepsy diagnosis accuracy problem has grown in direct proportion to home testing’s adoption. We’ve traded one barrier (lack of access to sleep laboratories) for another (inability to detect non-respiratory sleep disorders).

Mrs. K’s decade-long diagnostic odyssey didn’t need to last so long. With proper initial evaluation in a sleep laboratory, her narcolepsy would have been discovered years earlier. Appropriate treatment could have been started. But her story, and thousands like it, highlights a fundamental truth about modern sleep medicine: sometimes the most convenient path forward isn’t the right one.

As patients and advocates, we must demand better. Better diagnostic pathways that don’t rely solely on convenient technology with known blind spots. Better education for primary care providers about when home testing is—and isn’t—appropriate. Better insurance coverage for comprehensive laboratory testing when clinical suspicion warrants it. And better acknowledgment from the medical community that the gold standard, while better than nothing, still fails too many patients too much of the time.

What questions does your own sleep history raise? Have you been told you have sleep apnea but continue to experience crushing sleepiness despite treatment? Share your thoughts and experiences—your story might be the key that finally opens the door to diagnosis for someone else struggling in the dark.

FAQ

Q: What is home sleep apnea testing (HSAT)?

A: Home sleep apnea testing uses portable monitoring devices that patients wear overnight in their own homes to detect signs of obstructive sleep apnea. These devices typically measure airflow, breathing effort, blood oxygen levels, and heart rate—but critically, they do not measure brain activity or sleep stages, which are essential for diagnosing many sleep disorders including narcolepsy.

Q: What is narcolepsy?

A: Narcolepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by the brain’s inability to properly regulate sleep-wake cycles. It’s caused by the loss of neurons that produce hypocretin (also called orexin), a neurotransmitter that promotes wakefulness. The two main types are narcolepsy type 1 (with cataplexy—sudden muscle weakness triggered by strong emotions) and narcolepsy type 2 (without cataplexy). Both types feature excessive daytime sleepiness as their primary symptom.

Q: What is the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT)?

A: The MSLT is a diagnostic test performed in a sleep laboratory that measures how quickly you fall asleep during daytime nap opportunities and whether you enter REM sleep during those naps. You’re given five scheduled 20-minute nap opportunities spread throughout the day at 2-hour intervals. For narcolepsy, the test looks for: (1) falling asleep quickly (mean sleep latency less than 8 minutes), and (2) entering REM sleep during two or more of the five naps—a pattern called sleep-onset REM periods (SOREMPs).

Q: What is polysomnography (PSG)?

A: Polysomnography is an overnight sleep study performed in a sleep laboratory that comprehensively monitors multiple physiological parameters including brain waves (EEG), eye movements, muscle activity, heart rhythm, breathing patterns, and blood oxygen levels. Unlike home sleep tests, PSG captures complete information about sleep architecture, including sleep stages and REM sleep patterns, making it essential for diagnosing narcolepsy and other complex sleep disorders.

Q: What are SOREMPs (sleep-onset REM periods)?

A: SOREMPs are episodes where a person enters REM sleep within 15 minutes of falling asleep, which is abnormally fast. In healthy individuals, REM sleep typically doesn’t occur until 60-90 minutes after sleep onset. The presence of two or more SOREMPs during daytime nap testing (MSLT) is a key diagnostic criterion for narcolepsy, as it reflects the dysregulated REM sleep that characterizes the condition.

Q: What is hypocretin (orexin)?

A: Hypocretin (also called orexin) is a neuropeptide produced by approximately 70,000 neurons in the hypothalamus region of the brain. It plays a crucial role in promoting wakefulness and regulating REM sleep. In narcolepsy type 1, these neurons are destroyed through an autoimmune process, leading to very low or absent hypocretin levels. This deficiency can be measured through cerebrospinal fluid testing and provides highly specific diagnostic information for narcolepsy.

Q: What is cataplexy?

A: Cataplexy is a sudden, brief loss of muscle tone triggered by strong positive emotions such as laughter, excitement, or surprise. During a cataplectic episode, a person might experience anything from slight weakness in the knees to complete physical collapse, while remaining fully conscious throughout. It’s a distinctive feature of narcolepsy type 1 and is caused by the inappropriate intrusion of REM sleep’s muscle paralysis into wakefulness.

Q: What is EEG (electroencephalogram)?

A: An electroencephalogram is a test that measures electrical activity in the brain through sensors placed on the scalp. During sleep studies, EEG is essential for determining sleep stages, distinguishing between wakefulness and sleep, and identifying REM sleep patterns. Home sleep tests do not include EEG monitoring, which is why they cannot diagnose narcolepsy or other disorders that require assessment of brain activity and sleep architecture.

Q: What is the HLA-DQB106:02 genetic marker?

A: HLA-DQB106:02 is a genetic variant found in nearly all (95-99%) people with narcolepsy type 1, though it’s also present in approximately 25% of the general population without narcolepsy. This gene is part of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system involved in immune function. While a positive test doesn’t diagnose narcolepsy (because so many healthy people carry it), a negative test can help rule out hypocretin-deficient narcolepsy type 1.

Q: What is excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS)?

A: Excessive daytime sleepiness is an overwhelming urge to sleep during the day despite adequate nighttime sleep opportunity. It’s the primary symptom of narcolepsy but also occurs in many other conditions including obstructive sleep apnea, insufficient sleep syndrome, and certain medications. This symptom overlap is a major reason why narcolepsy is frequently misdiagnosed—the shared symptom of EDS can lead to sleep apnea being identified while narcolepsy goes undetected.

Q: Why do home sleep tests have poor accuracy for narcolepsy diagnosis?

A: Home sleep tests fundamentally cannot diagnose narcolepsy because they don’t measure the key physiological features of the disorder. Narcolepsy diagnosis requires assessment of how quickly REM sleep occurs, how sleep stages are structured, and whether abnormal sleep-onset REM periods happen during daytime—none of which can be measured without EEG monitoring of brain activity. Home tests only measure breathing and oxygen levels, making them useful for sleep apnea but completely inadequate for narcolepsy evaluation.

Q: Can you have both narcolepsy and sleep apnea simultaneously?

A: Yes, and this comorbidity is surprisingly common. Research shows that 25-51% of people with narcolepsy type 1 also have obstructive sleep apnea. When both conditions are present, home testing will detect the sleep apnea but miss the narcolepsy entirely, leading to incomplete treatment. Patients may experience some improvement from CPAP therapy (which treats the sleep apnea) but continue to have significant symptoms from the undiagnosed narcolepsy.

Q: What should I do if I suspect narcolepsy?

A: Request a referral to a sleep specialist for comprehensive evaluation in an accredited sleep laboratory. Do not rely on home sleep testing. Before your evaluation, keep a detailed sleep diary for at least two weeks documenting your sleep schedule, daytime sleepiness episodes, and any unusual symptoms. Be prepared to discuss all symptoms including cataplexy (sudden muscle weakness with emotion), sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucinations (vivid dreams when falling asleep), and disrupted nighttime sleep—not just excessive sleepiness.

Q: How long does it typically take to get a narcolepsy diagnosis?

A: Unfortunately, diagnostic delays of 8-15 years from symptom onset are still common, with patients typically seeing multiple physicians before receiving an accurate diagnosis. This delay is one of the longest for any medical condition and is exacerbated by the increasing use of home sleep testing that cannot detect narcolepsy. The goal of narcolepsy advocacy organizations is to reduce this delay to one year or less through improved awareness and appropriate testing protocols.

Q: Are there any biomarkers besides MSLT that can diagnose narcolepsy?

A: Yes, though they’re not universally available. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing for hypocretin-1 levels (obtained through lumbar puncture) is highly specific for narcolepsy type 1, with levels below 110 pg/mL being diagnostic. HLA-DQB1*06:02 genetic testing can provide supporting evidence. However, these tests are typically reserved for cases where MSLT results are ambiguous or when patients cannot discontinue medications that interfere with MSLT interpretation.

Q: Is the MSLT test reliable?

A: The MSLT has moderate reliability for narcolepsy type 1 (with cataplexy) but poor reliability for narcolepsy type 2 (without cataplexy). Test-retest studies show that only about 30% of people diagnosed with narcolepsy type 2 on their first MSLT have positive results when retested. False-positive rates of 2.5-4.7% and false-negative rates of 7-20% have been documented. Multiple factors can affect results including medications, sleep deprivation, circadian rhythm issues, and testing conditions, which is why preparation and expert interpretation are crucial.